One of the interesting things about games where players have hidden information, like poker or crib, is how hard it is to solve them. Ultimately this comes down to the fact that counterfactuals, things that could have happened but didn't, affect the optimal strategies. Unlike games of perfect information, such as chess and backgammon, you can't find the optimal strategy by just recursing down the game tree the way minimax and expectiminimax do. The sub-trees interact.

In this post, in order to give an idea of how counter-intuitive strategies for imperfect information games can be, I'll present and analyze a simple game. Then I'll point out how crazy following the optimal strategy looks.

The Game

I call the following game "stormy fate". It's not quite the simplest game I could have used, but it's close.

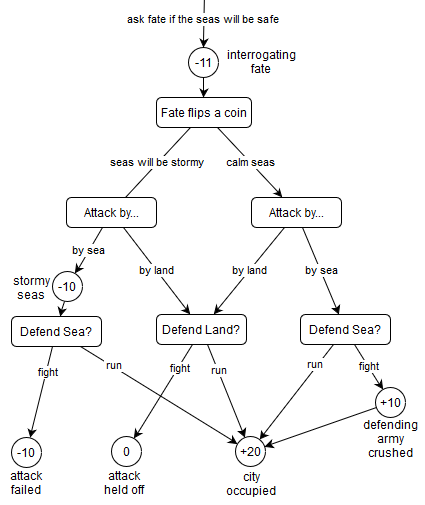

Stormy fate starts with an attacker asking fate if the seas will be safe. Fate flips a coin to decide, then tells the attacker if there will be a storm. After receiving that information, the attacker has to decide whether to attack the other player (the defender) by land, or by sea. The defender, who is not aware of whether there was a storm but will see how the attacker is approaching, has to choose between standing their ground and running away.

The goal of the game is to accumulate the most points. For daring to interrogate fate, the attacker starts the game by paying an 11 point penalty. Questioning fate further, by sailing seas fated to be stormy, would cost an additional 10 points. On top of that, storms weaken attacks. If the defender fights a storm-battered fleet, the defender wins the battle and +10 points. This is risky for the defender, though, because if the seas were calm then the attacker will win the battle for +10 points and occupy the city for +20 points.

The defender's alternative to fighting is running away, but that leaves the city defenceless. The attacker will occupy it for +20 points. The defender also has the choice of fighting or running when the attacker approaches by land, but the formidable walls can hold off a land attack without any points changing hands.

Here's the game tree, for reference:

We want to find an optimally resilient strategy for the attacker. The one hardest for a defender to exploit.

Puzzle: Is there an attack strategy where the attacker's expected change in points is positive, relative to any possible defender?

Analysis

Analyzing the game is a lot easier if we drop the narrative and break things down into cases:

| Fate | Attacker | Defender | Outcome |

| storm | land | run | +9 |

| storm | land | fight | -11 |

| storm | sea | run | -1 |

| storm | sea | fight | -31 |

| calm | land | run | +9 |

| calm | land | fight | -11 |

| calm | sea | run | +9 |

| calm | sea | fight | +19 |

A strategy is just an assignment of probabilities to each possible decision. The attacker and defender each have two decisions to make. The attacker decides how often to attack when the seas are stormy, and how often to attack when the seas are calm. The defender decides whether to fight or flee when the attack comes by land, and whether to fight or flee when the attack comes by sea. (Recall that the defender doesn't know whether the seas were stormy. It may be possible to infer that based on where the attack is coming from, but otherwise the defender's strategy is forced to be independent of sea storminess.)

Together the strategies determine the expected change in points $E$. We just scale each outcome's point change by the probabilities that lead to it, and sum up. So:

- Let $p$ be the probability of the attacker attacking by land when it's stormy.

- Let $q$ be the probability of the attacker attacking by land when it's calm.

- Let $a$ be the probability of the defender running when attacked by land.

- Let $b$ be the probability of the defender running when attacked by sea.

- Define $\overline{x}$ to be $1-x$, the complement of $x$.

- Then $E = \frac{1}{2} \left(+9 p a - 11 p \overline{a} - \overline{p} b - 31 \overline{p} \overline{b} +9 q a - 11 q \overline{a} + 9 \overline{q} b + 19 \overline{q} \overline{b} \right)$

The attacker wants to maximize $E$. The defender wants to minimize it. Because the goal of the puzzle is to gain points against all defensive strategies, we can pretend that the defender has access to the attacker's strategy. A good analogy here is to think of the attacker as a casino machine that can't be updated. The defender is going to reverse engineer the machine, find any flaws, and exploit them mercilessly. For our purposes, this just means the defender gets to use $p$ and $q$ when choosing $a$ and $b$.

To decide what $a$ should be, the defender inspects the derivative of $E$ with respect to $a$:

$\frac{dE}{da} = \frac{1}{2} \left(+9 p + 11 p +9 q + 11 q \right) = 10 p + 10 q$

When the derivative is positive, the attacker will gain points whenever $a$ is increased. So in that case the defender wants $a$ as low as possible, and should set it to 0. Conversely, when the derivative is negative, the defender should set $a$ to 1. The value of $a$ goes discontinuously from $0$ to $1$ when the sign of the derivative changes. We can represent that as $a = H(-p - q)$, where $H$ is the heaviside step function.

We repeat the same procedure for $b$. First, compute the derivative:

$\frac{dE}{db} = \frac{1}{2} \left( -\overline{p} + 31 \overline{p} + 9 \overline{q} - 19 \overline{q} \right) = 10 - 15p + 5q$

Then flip the sign, remove the common factors, and use the heaviside step function. We find that $b = H(3p - q - 2)$.

Now let's rearrange the expected value formula so we can plug in our formulas for $a$ and $b$. Start by expanding $\overline{a}$ and $\overline{b}$, and gathering terms:

$E = \frac{1}{2} \left(a \left( +9 p + 11 p + 11 q + 9 q \right) + b \left( -\overline{p} + 31 \overline{p} + 9 \overline{q} - 19 \overline{q} \right) - 31 \overline{p} - 11 p - 11 q + 19 \overline{q} \right)$

Simplify the terms:

$E = \frac{1}{2} \left(a \left( 20 p + 20 q \right) + b \left( 20 - 30 p + 10 q \right) - 12 + 20 p - 30 q \right)$

Insert the formulas, and extract factors so the heaviside functions get multiplied by their own argument:

$E = \frac{1}{2} \left(-10 H(-p - q) \left( - p - q \right) - 10 H(3p - q - 2) \left( 3p - q - 2 \right) - 12 + 20 p - 30 q \right)$

Now use the fact that $H(x) x = x \uparrow 0$, where $a \uparrow b = max(a, b)$.

$E = \frac{1}{2} \left(-10 ((-p - q) \uparrow 0) - 10 ((3p - q - 2) \uparrow 0) - 12 + 20 p - 30 q \right)$

Finally, get rid of that pesky factor of a half:

$E = 10p - 15q - 6 - 5 ((-p - q) \uparrow 0) - 5 ((3p - q - 2) \uparrow 0)$

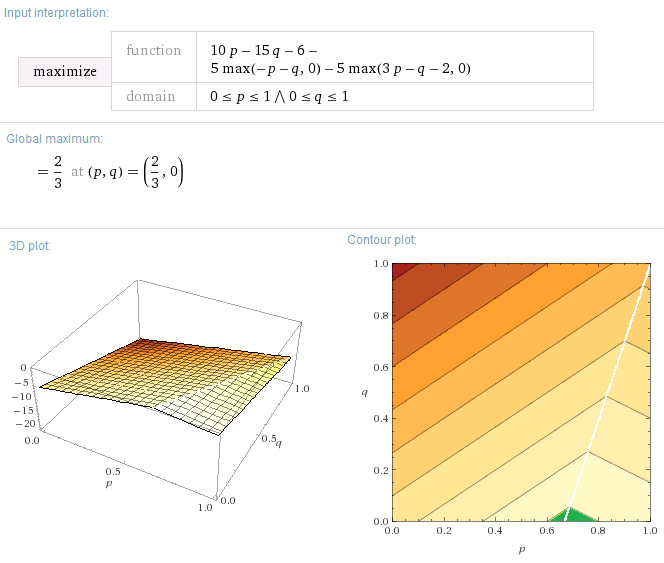

Great! Now we have a compact formula that only involves $p$ and $q$. The least-exploitable attacker strategy is whatever values of $p$ and $q$, both required to be between 0 and 1, maximize $E$. We don't even have to do an exhaustive search of the space: all the cases are linear, so we just need to check critical points.

There's a critical point wherever two critical lines intersect. In this case our critical lines include not just the four lines bordering the unit square, but also the lines $p=q$ and $3p = q + 2$, because they define the borders where the the maximum operators switch which operand is returned.

We find that the critical points are $(0,0)$, $(0,1)$, $(1,0)$, $(1,1)$, and $\left(\frac{2}{3}, 0 \right)$. The maximum is at $\left(\frac{2}{3}, 0 \right)$, where $E$ is $\frac{2}{3}$. Given $p=\frac{2}{3}$ and $q=0$, we can also determine that $a = H(-\frac{2}{3} - 0) = 0$ and that $b = H(3 \frac{2}{3} - 0 - 2) = H(0) \in [0, 1]$.

Translated back in terms of the word problem, these numbers mean that the attacker will always attack by sea when the seas are calm, but only attack by sea $\frac{1}{3}$ of the time when it's stormy. The most exploitative defender against this attack strategy is one that always fights land attacks, but may arbitrarily fight or run from sea attacks without affecting the expected outcome. Let's arbitrarily say the most exploitative defender always fights any attack.

A slightly easier way to find the maximum is to just plug the problem into wolfram alpha:

(Note: I made non-negligible edits to the above screenshot to make it clearer.)

The small green area in the contour plot is the space of strategies with positive returns.

Bonus puzzle: Can you modify the game's payoffs so that the positive returns area doesn't touch the sides?

Counter-intuitive Sub-Games

Put yourself in the shoes of an attacker who's just been told the seas are going to be stormy. The "calm" part of the game tree is unreachable. The -11 penalty for interrogating fate has already been applied. What do the remaining payoffs for our choices look like?

| storm | land | sea |

| run | +20 | +10 |

| fight | 0 | -20 |

If you were presented with this game, by itself, what would the solution be? Well, the fight row clearly dominates the run row. The defender always does better by fighting, so that's what they'll do. Also, the land column dominates the sea column (even given that the defender gets to play second). Clearly the optimal strategy in this sub-game is to always attack by land. Attacking by sea is tantamount to just throwing away 20 points.

Except that, in the larger game, the optimal strategy is not to always attack by land. One third of the time you have to stand in front of your sailors, with the sky already rumbling in the distance, and tell them to mount a doomed attack. While they look at you like you are the most absurdly stupid person ever.

You might think that attacking by sea when it's stormy is a way to bluff the defender. Well, sort-of, but remember: an optimal defence against this attack strategy is to always fight. The defender is not going to run from our attack. They are going to crush it.

So why the heck are we throwing these sailors' lives away?

Because if we didn't, the enemy would run when we attacked by sea. The goal is not to make the stormy seas attack look strong, it's to make the calm seas attack look weak. We want the extra ten points for crushing the defending army before occupying the city, and suiciding now and then just happens to do the trick. Choosing to attack by sea when it's stormy isn't a bluff, and it isn't feigning weakness, it's creating the counterfactual opportunity to feign weakness.

Playing out this strategy is especially strange when the game is only going to be played once. You know you'll never see the benefits of creating that counterfactual opportunity. Saying you purposefully lost the war so that you could have won it is somehow... not very convincing. But if you won't purposefully lose the war, if you can't stick to the optimal strategy, then opponents will use that against you and you'll expect to lose more often.

Summary

Incomplete information games are hard to solve (it takes doubly-exponential time in the worst case), because their sub-parts interact in complicated ways. Being able to precommit to following strategies that have sub-cases where you work against your own interests is an important ingredient in optimal play.